An always-stocked bowl of chocolate in her office makes Dianne Lynch’s open-door policy even more appealing.

Lynch, the president of Stephens College since June 2009, laughs at her own reference to the chocolate bowl. It’s the same easy tone Lynch uses to deflect and share any credit for the liberal arts college’s strength and vitality, even as other private colleges — and certainly public institutions of higher education — struggle with dried-up funding, shrinking enrollment, and the constant need to compete for new students.

Stephens, a Columbia mainstay since 1833, added a physician assistant program to its health sciences department last summer and continues to receive accolades for fashion and design programs (they’re also the first women’s college to launch an eSports department). The new physician assistant program got a boost from a $1 million gift from 1954 alumna Phyllis Henigson, the result of Lynch’s pitch for seed money — “a lot of seeds,” Lynch said during a gift recognition event last summer.

And there’s more.

“Where do you want to start?” Lynch says about the latest news and developments at Stephens College. “How much time do you have?”

Her bullet point list of highlights reflect a small college — full-time enrollment exceeded 800 for the 2017-2018 academic year — that knows its identity, what it does well, and why it’s necessary to embrace, not avoid, change. The shifting landscape of higher education offers few certainties and abundant challenges.

“If you’re not comfortable with change, this is probably not the place for you,” Lynch says. “I always tell our community that if you feel the ground slipping out beneath your feet, you learn to tap dance.”

In any market, whether an organization is an “enormous player” or a “smaller, unique, specialized organization” – a comparison of Stephens to its larger higher-ed counterparts in Columbia and elsewhere — Lynch says the institutions that thrive are those “that know exactly what their strengths and their market are.”

“It’s much easier to be nimble and dynamic and responsive when you’re small,” Lynch adds. Stephens has embraced the sense of community that permeates the local campus and its satellite facilities. Those include a partnership with the Jim Henson Studios, in Los Angeles, as home to their degree in screenwriting, to a now 60-year-old theatre program and new artist village — the result of a major fundraising and building project — in Okoboji, Iowa.

“We’re a small, residential women’s college in the heart of a university town. We know the type of young woman that we are best situated to serve,” Lynch says. “We are not all things to all people. We have no interest in being that.”

Staying on Track

The college just finished a five-year strategic plan, a “dynamic, living document” that looks to build on the creative arts and health sciences programs under the Stephens umbrella with the traditional performing arts and fashion design programs.

The Business of Fashion, a fashion industry group, has named the Stephens program second in the world, in competition with places like Manila, Tokyo, London, and Paris. The School of Performing Arts was ranked sixth in the country by the Princeton Review.

Tuition and fees for 2017-2018 will average a little over $30,300. Based on room and board selections for a college that bills itself as the “No. 1 pet-friendly campus” in the country, the total annual cost for a Stephens College student will be between $38,600 and $42,900. The college has a 65 percent acceptance rate, is 96 percent female, and has a student-faculty ratio of 10-to-one.

“I think that’s among our greatest strengths,” Lynch says. “Stop any student and ask why they love Stephens — they would tell you that it’s about their relationships with our faculty. And, yes, they like that the president wears red shoes and there’s always chocolate in my office. But they don’t come to Stephens for that.”

Environmental law attorney Aimee Davenport earned her undergraduate degree from Stephens in 1998, well before Lynch came on the scene eight years ago.

“The chocolate bowl is huge. Of course I’ve eaten from it,” Davenport says. She has forged a strong relationship with Lynch while nurturing a seemingly lifelong connection with Stephens. She sported a Stephens T-shirt as a 4-year-old in the ’70s, when her dad was taking a correspondence course there. More recently, Davenport is the immediate past president of the Stephens College Alumni Association board.

As a student, Davenport found Stephens to be the perfect place to be both an athlete and musician. “Stephens offered enough of everything,” she says. Davenport fell in love with the college and with Columbia.

And she’s a vocal, ready supporter of the college president.

When Lynch demurs, reluctant to take credit for Stephens’ progress and prestige — “credit belongs to everyone here,” she says — the deflection is genuine and sincere, Davenport says. But she has no hesitation in where to direct those kudos. Lynch built on progress that was under way via previous president Wendy Libby, Davenport says, taking the next steps in giving the college “a name and an identity beyond Stephens’ walls.”

“She engaged the alumni and the students and worked to give Stephens a spot in the larger community,” she says. “All that credit needs to go to Dianne.”

A Humble Look Forward

Perhaps the one award ceremony that illustrated Lynch’s credit-deflection was the Athena Leadership Award event in April 2016 in Lela Raney Wood Hall on the Stephens campus. After Lynch accepted the award to a lengthy standing ovation, she took the microphone and asked for a second standing ovation for the other two award finalists. Lynch went on to extol the contributions of the other finalists and added that the Athena Award – a high honor for career success and supporting women in business – was “without a doubt, the most affirming … and cherished award I could receive.”

Now, asked another question about the role she has played in Stephens’ growth over the last few years, Lynch says: “I think Dianne Lynch has had something to do with being part of an extraordinary team. Perhaps more than at other institutions, this is a team effort, and we are entirely a community. There isn’t anybody on this campus who doesn’t deserve recognition of the fact that they, too, have contributed.”

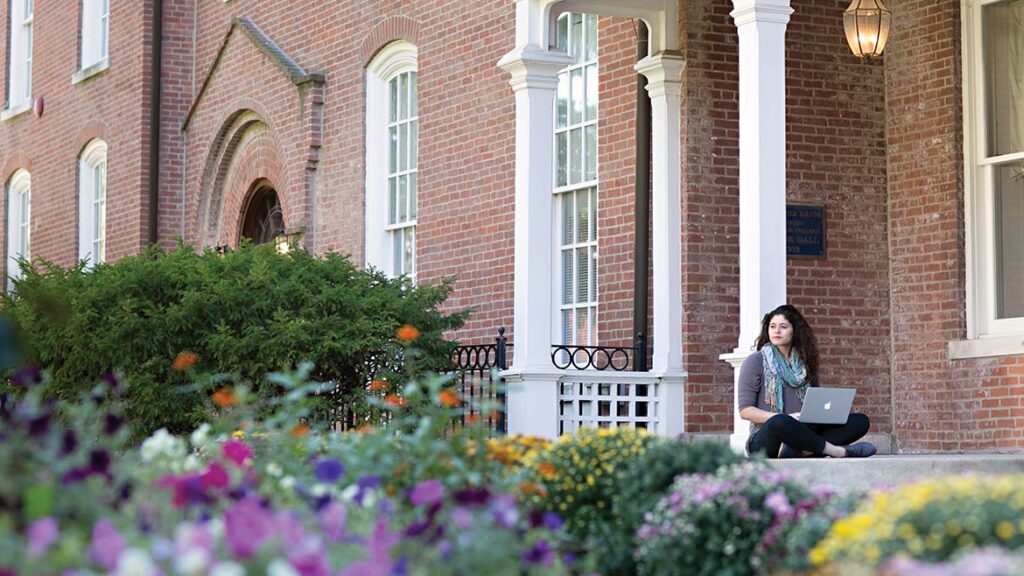

Lynch and Stephens also take pride in the college’s visibility at the intersections of College Avenue and Broadway — one of the gateways into downtown Columbia. At the beginning of the summer, the campus hosted 1,200 visitors to the Unbound Book Festival.

Davenport likes the forecast for her alma mater. “I think Stephens is going to continue to produce forward-thinking leaders,” she says. “[It] was a really transformative experience for me. . . . Stephens will only become stronger. I don’t see the momentum stopping.”

Lynch recently headed to Okoboji, eager to see the culmination of summer theatre work and hopeful that her cargo was safe from the elements during the 7½ hour drive. She knew there was an expectation for her visit.

“I take great, big tubs of chocolate,” she says.