Grandson successfully campaigns for Columbia veteran to join George Washington as a Congressional Gold Medal honoree.

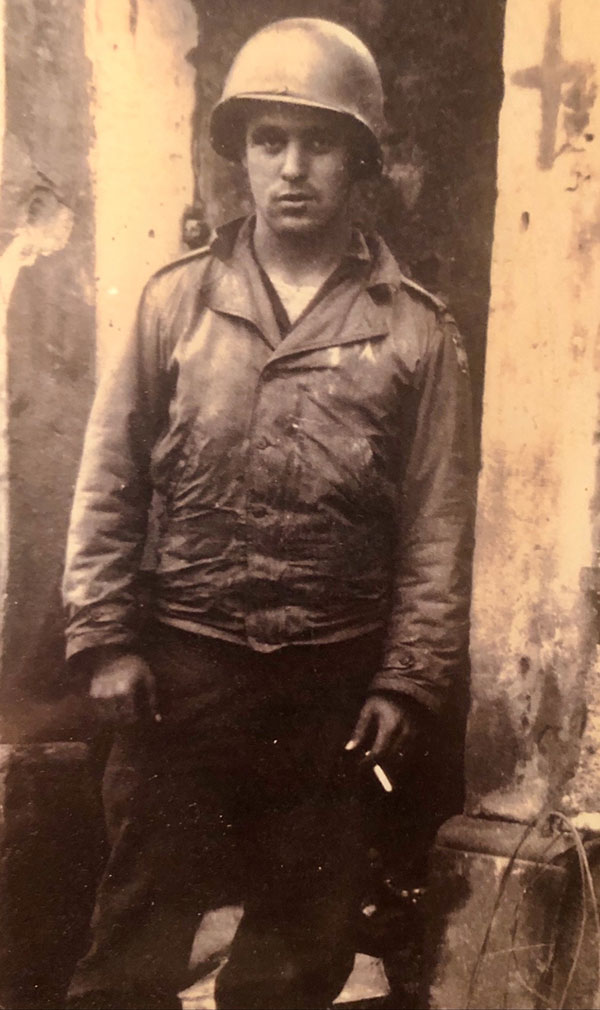

Private John J. Williams had a secret. For at least fifty-two years, the World War II Army radio man was sworn to secrecy, unable to add specific details to his account of being among the 156,000 Allied forces who stormed the beach at Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944.

D-Day. Also known as “Operation Overlord,” it was the singular, bloody event that historians point to as the beginning of the end of World War II. And Pvt. Williams — who later managed a Columbia, Missouri, hardware store and worked for the University of Missouri — was there, arriving on the third wave of troops that eventually liberated France by the end of August 1944, sending the Nazis back to Germany.

Though Pvt. Williams was there in full view, his cloak-and-dagger role remained hidden to the public until 1996, when President Bill Clinton declassified the true nature of Williams’ work as part of what is now known as the “Ghost Army.”

The Ghost Army was a complement of some 1,100 soldiers, but their actions made the Nazis think they were a 20,000-strong unit.

John J. Williams was posthumously honored March 21 in Washington, D.C., during a Congressional Gold Medal ceremony at the U.S. Capitol that honored all 82 officers and 1,023 enlisted soldiers in the Ghost Army. His grandson and son — Columbia gastroenterologist Dr. Michael Williams and retired Columbia veterinarian Dr. John S. Williams — accepted the posthumous medal, fourteen years after John J. Williams’ death.

The ceremony — almost scuttled due to a threatened government shutdown over rancorous and stalled federal budget talks — was years in the making, and it put Pvt. Williams in a rarified, patriotic company.

The first Congressional Gold Medal recipient was George Washington.

“If you knew my dad, you’d know that it was hard for him. He was an Irishman; he loved to spin tales.

Dr. John S. Williams, retired Columbia veterinarian

But he didn’t say a thing. He was a very good soldier.”

The Ghost Army used inflatable tanks, fake radio traffic (thanks in part to Pvt. Williams), loudspeakers that blared the sounds of military vehicles and trucks, and fake uniforms and camouflage to bewilder Nazi Germany axis forces. Williams helped deploy those strategies as a member of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops along with the 3133rd Signal Service Company.

“I remember growing up, even after it got declassified, Grandpa didn’t talk about it much or at least the importance of it,” Michael Williams said. “He talked about being a radio man in the war; I knew he was at Omaha Beach on D-Day. But when you’re a kid, you don’t realize how big that was.”

Michael was born and raised in Columbia — a “Boone Baby” — and he graduated from Rock Bridge High School in 1995. He went to Mizzou for undergrad medical school and graduated from the University of Missouri School of Medicine in 2003. After a gastroenterology residency and then seven years on staff as a gastroenterologist at Northwestern in Chicago, Michael and his wife and twin daughters moved to Columbia where he has been on staff at GI Associates since 2017.

Michael says he basically stumbled upon the Ghost Army Legacy Project, a process led by Rick Beyer to officially recognize and memorialize the role that John J. Williams and 23rd Headquarters Special Troops played in the D-Day invasion and other pivotal World War II battles. Michael defers the credit for that project to Beyer.

“If it wasn’t for him, this never would have happened,” Michael explained. “It was a true grassroots effort. No PAC or donations to Congressional leaders. It was just family members of the ghost army reaching out to their elected officials and seeing if they would support the bill” that proposed striking Congressional gold medals for their once-secret military service.

“We didn’t even know the term ‘Ghost Army.’ I never heard Grandpa say that,” Michael added.

His father, Dr. John S. Williams, was a veterinarian for forty years at Horton Animal Hospital, working with that practice’s founder, Jack Horton. John S., who was 11 when the Williams family moved to Columbia, recalls visiting his parents just after the Ghost Army activity was declassified.

“Dad said, ‘Look what I just got in the mail,’” pointing to the letter that said he could now talk about his under-the-radar World War II activity. John S. obviously had no idea what the letter was about, and he hadn’t heard his father talk much about actual battles and military campaigns, which was surprising because, well, his father was a talker.

“If you knew my dad, you’d know that it was hard for him,” he said. “He was an Irishman; he loved to spin tales. But he didn’t say a thing” about the Ghost Army. “He was a very good soldier.” At the end of the war, Ghost Army soldiers received a letter from Army General Dwight D. Eisenhower, strictly warning against talking about their deception operations. John S. isn’t exactly sure that the next line was, “Or you’ll be hanged” for committing a treasonous act, but the letter had that much weight.

In the fourteen years before he died, John J. Williams told his son and grandson more about his time in the military, but the stories were usually focused on the friends he made and the time they spent together.

“Dad created fake radio traffic. They were trying to confuse things for the Germans, to let them think there was a lot more power associated with” the fake activity, his son said. “They made themselves look and sound like thousands.”

He remembers one story his father told him about the unit being encamped next to a river, holding a position with “rubber tanks and sounds of tanks moving.” There were only a few hundred men. During the day, many of the soldiers went to the river to fish, and the Germans were on the other side

“They would wave at the Americans,” John S. said. “If they’d have known there were only a couple of hundred of them, if they had been found out — well, it wouldn’t have been much of a fight.”

John S. said his father never talked about being frightened.

“If it ever worried him, he never mentioned that,” he added. “When you first hear about” the ghost army activity, “it’s not blood and guts; it’s just something they did. It’s what didn’t happen that’s the significant thing — because of what these guys were doing.”

John J. was from Adair County in northeast Missouri; a farm kid with an eighth-grade education. He became a lumber yard manager and the Williams family moved to Vandalia and then to Columbia in 1958. He managed Benson Lumber Co. on the Business Loop, a property that John S., now 76, says is a Kia automobile dealership. John J. also developed the lumber department for Westlake Hardware, then went to work for the University of Missouri as an estimator for construction projects.

In some ways, Michael says, his grandfather seemed to treat and recall his military service — including storming the beach at Normandy — as a job without particular valor or historical significance. But that was not a sign of disrespect or disingenuous humility.

“I think his perception of the war was this is what you did. This was your job, what you’d been trained to do,” Michael explains. “He wanted to do his job and come back home and start a family.”

History, however, champions the significance and sacrifices of The Greatest Generation.

“This is history,” Michael said. “There’s only a handful of these guys that are still alive. We’re getting far enough away now that if you don’t document these things, they might get lost. They helped shape our country’s history.”

Michael is passionate about the role and sacrifices of his grandfather and all the men and women who fought to preserve democracy and freedom.

“I’m almost 47,” he added. “I feel like I’m old enough to finally wrap my hands around the importance of what they did. I can’t tell you how proud we are to know his name is on a Congressional Gold Medal with people like George Washington. How can you top that? It’s something our family will always be very proud of.”