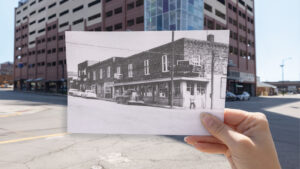

Downtown’s Sharp End has a complicated history. Photos by Anthony Jinson

At the start of April 2015, managing editor Jim Robertson called me to his office at the Columbia Daily Tribune and closed the door.

He calmed my fear that I was about to be fired by giving me a special assignment. I was going to drop everything to produce a special section on Sharp End.

“What’s Sharp End?” I asked.

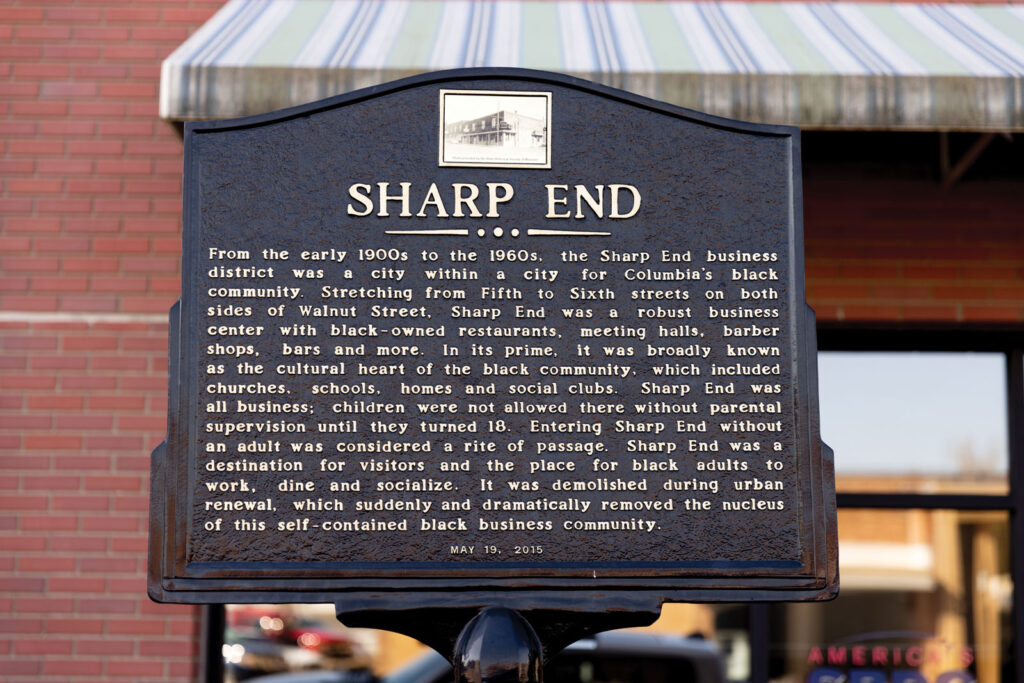

My answer was the same that the vast majority of Columbians, white or Black, would have given that day. I had no idea that for fifty years, a business district along Walnut Street provided Black residents the kinds of services otherwise closed to them by legal and cultural segregation.

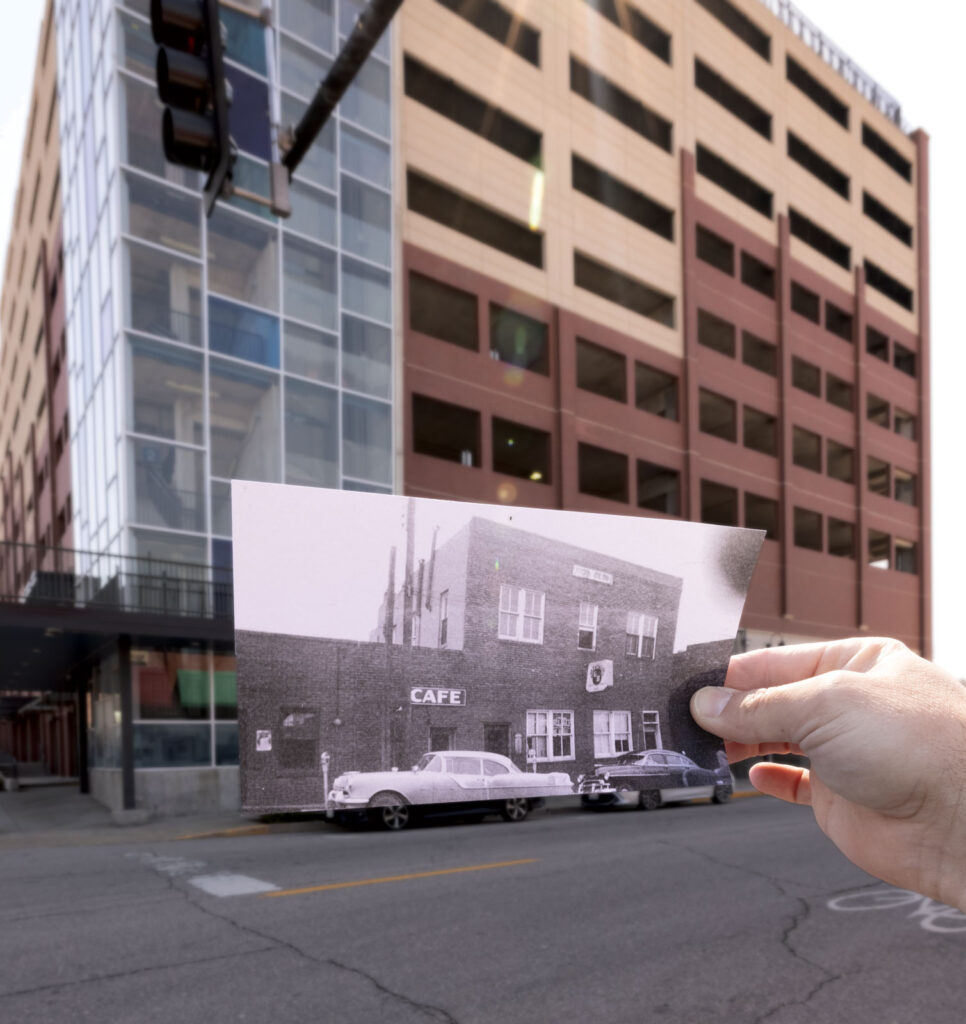

All I had known, since arriving in Columbia in 1983, was that the block between Fifth and Sixth Streets was home to the Columbia post office, with a parking lot — later a giant parking garage — filling the block across the street.

My ignorance was due, in large part, to me being one of many Columbians who came from somewhere else. In the fifty-five years after Sharp End was demolished — one of the many tragedies of so-called “urban renewal” — Columbia tripled in size; people were attracted in large part by jobs linked to the University of Missouri and state government.

My lack of knowledge was also due to the story of Black Columbia being ignored by the larger community.

“Nobody knew it,” said Barbra Horrell, co-chair of the Sharp End Heritage Committee, in a recent interview. “They didn’t talk about it anymore.”

Even ten years later, when a new venture, The Shops at Sharp End, is in place to incubate new businesses, the director isn’t quite sure what she’s trying to revive.

“I didn’t even know anything about the Sharp End, I didn’t even know anything about the businesses around here,” said Tiowanna Warrick, who moved to Columbia twenty years ago.

“Even just living in Columbia, it just wasn’t a conversation that was brought up,” she conceded. “I definitely didn’t hear anything about this until I actually started working here.”

The Life of Sharp End

In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, more than one of every four residents of Boone County was Black. But only fifty-three of those 5,087 people were free.

Emancipation started two large movements. The first was from the countryside into Columbia, where the Black population more than doubled by 1880. The next phase was a seventy-year exodus where Boone County lost 40 percent of its Black population.

The combined effect meant that by 1910, more than half of the Black residents of Boone County lived in Columbia while the Black proportion of the county population as a whole was one in eight. Census reports show how, within Columbia, strict segregation limited Black residents to the area along Flat Branch Creek, between Garth Avenue and Eighth Street, with a few outlying neighborhoods.

The demand for businesses that would serve that growing population found a voice in the Columbia Professional World, a newspaper serving the Black community and launched by Rufus Logan in 1901.

“The population of Columbia is 50 percent negroes without a single negro business house,” Logan wrote in a November 15, 1901, editorial. “A joint stock company well organized and properly managed should prove to be quite a profitable enterprise for Columbia negroes. All that is necessary is for some good energetic man to take the initiative in founding such a project.”

In 1909, under the leadership of Rev. Beriah Cain, the congregation of St. Luke Methodist Episcopal Church built a new stone chapel on the northeast corner of Fifth and Walnut streets. There was new construction as well on the southeast corner. Development of the block into a commercial district began in 1910. By the mid-1910s, a two-story brick building offered street-level storefronts, with apartments on the second floor.

An existing example of the type of construction is the building housing Tony’s Pizza Palace on the southwest corner of Fifth and Walnut Streets. During the Sharp End era, it was home to a barber shop. It is also one of the only buildings in the Sharp End district that was, and is, Black-owned by the Tibbs family.

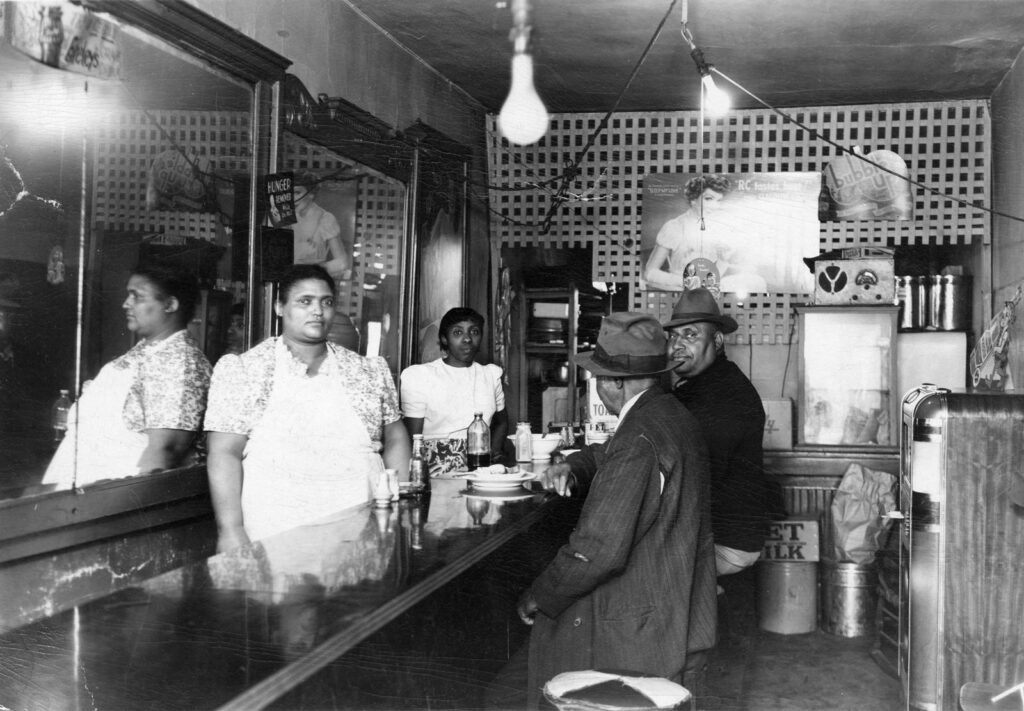

The businesses that came first took care of personal needs that could not be found for blacks in a similar Columbia setting. A pool hall, a barbershop, and a restaurant were the first to open. Sharp End was where adult Black residents sat down to meals, enjoyed bands in a crowded nightclub, attended meetings of fraternal organizations, and lived in dozens of apartments.

By the 1940s, Sharp End was in full flower. Names that wouldn’t sound out of place in a gritty film noir of the same era — the Green Tree Tavern, The Dreamland Cafe, Alton “Mr. Heavy” Patton and David “Pig” Emory — helped give Sharp End its character.

The Green Tree Tavern was a nightclub where, because there were no liquor-by-the-drink sales in Columbia, patrons asked for bowls of ice and a glass, and perhaps a mixer or chaser, to go with the spirits in their pocket flask. It operated under a variety of names for more than thirty years.

Exactly how Sharp End got its name is lost to history. It was in use by 1917, when a Columbia Missourian report about the case of a bootlegger noted he was arrested “at Fifth and Walnut Streets, known to its frequenters as ‘Sharp End.’”

The late Sehon Williams, who played jazz at the Green Tree before being drafted for World War II, told me in 2015 that it was because men carried switchblade knives and razors to defend themselves. Other versions point to the nightlife and stylish clothes worn to the club.

A 1938 University of Missouri master’s thesis on Columbia’s Black churches recorded St. Luke’s was built “at the corner of Fifth and an unnamed street. Sometimes this street is called Sharp Avenue.”

It was not really a street, the thesis stated, but a north-south alley east of Fifth Street.

That’s the version Horrell thinks is true. The apartments that stretched north from Walnut Street in a building that also housed the Elks lodge were accessed on the alley mentioned in the thesis, she said.

“Behind where the post office is, you went in that way up the alley, and you went upstairs to the apartments,” Horrell said.

Horrell lived on Third Street — today Providence Road — where her uncle, Ben Havey, operated an inn listed in the Negro Travelers’ Green Book. The kids who attended Douglass School bought sodas and ice cream at the Freeze King and families bought groceries at the Third Street Market.

A white merchant brought clothes to Black residential areas; in downtown stores owned by white merchants, a Black woman could purchase a dress but not try it on or return it.

“We had everything everybody else had,” Horrell said. “We just had it in our neighborhood.”

Sharp End, however, was different. Closed to anyone under 18, it was the focus of adult life. (“Adults-only” had a different, less sexualized connotation back then.) Horrell was never old enough to go on Sharp End herself. She and her friends would get as close as they could.

“There was an empty lot, and that’s where we would all hang out, because we couldn’t go to Sharp End,” she said. “But we were teenagers, right? So we would hang out there on Saturday and Sunday. That’s where Black kids hung out, because that was when we were still segregated.”

A big celebration each year for Columbia’s Black community was August 4, chosen to symbolically show that their independence had been delayed. During the day, family-oriented events took place on the grounds of Douglass School.

At night, the focus shifted to Sharp End.

“There would be one, well, it would be, I guess, two days, because one day they would close off Sharp End from Fifth to Sixth Street,” Williams said in a 2006 oral history interview with Gary Kremer, executive director of the State Historical Society of Missouri. “Be open gambling, dancing, drinking, whatever you wanted to do. Even some of the white policemen would come down and join in.”

Sharp End vanished in 1961, erased from the landscape — and the city’s collective memory — with a dismissive reference in the plan approved in 1958 by the Columbia Land Clearance and Redevelopment Authority.

“The alley to the south of Walnut between Fifth and Eighth streets further delimits the project area because it divides the undesirable property fronting on Walnut from the desirable property to be retained fronting on Broadway,” the report stated.

Today, planners would call Sharp End a mixed-use community. The only difference between the properties facing Broadway and those facing Walnut was the skin pigmentation of the proprietors and patrons.

What was lost to the collective memory of Columbia is both a wound that hasn’t healed and a cherished memory among those who lost businesses and homes to land clearance. The resentment was over the resulting loss of family wealth and independence as businesses closed because they had no adequate place to relocate.

The impact was doubly hard on families that lost homes on Switzler, Pendleton, and other streets that became the site of public housing projects.

“I remember so well the pride Black families had, because they had their homes, whatever size they were, and how many kids they had in them,” Horrell said.

The Tribune’s special section was issued the day the Sharp End Heritage Committee erected a marker in front of the towering parking garage that occupies the most important block of Sharp End.

The resurrection of Columbia’s Black history has continued. Sharp End is now stop 23 on the 29-stop African American Heritage Trail, which includes stops at the places where Columbia’s first Black businessman, John Lange Sr., had his pre-Civil War butcher shop and its richest businesswoman of any race in the early 20th century, Annie Fisher, built her fine home on Park Avenue.

It also visits the spot on Stewart Road where James Scott was lynched in 1922.

“We worked our butts off” to establish the trail, Horrell said.

But she wants to be clear — Sharp End was a distinctive location on Walnut Street. The trail is a path into the other stories of Black Columbia.

“The Heritage Trail is the Heritage Trail. Sharp End was Sharp End. They are not the same,” Horrell said. “Sharp End was Black businesses. The Heritage Trail is the rest of Black Columbia that had had some presence that you all didn’t know about.”

What made Sharp End?

Sharp End thrived because it was a refuge from the crippling segregation that closed doors to opportunity; drew lines where Blacks could not live or be found at large after dark; or put their lives in danger from lynch mobs.

Even as it grew in importance in the lives of Columbia Blacks, the outward migration diminished the Black portion of the city and county. By the time the land was being cleared, almost a hundred years after emancipation, fewer than one in sixteen residents of Boone County was Black.

Young Black people didn’t see a future in Columbia, Horrell said.

“Most of the kids, when they graduated from high school and they went to college, they went to historical black colleges, which taught them there’s no place to go back home,” she said. “You saw no Black lawyers. You saw nobody like us, unless they were in the neighborhood. Even our Black doctors had left here and gone someplace else.”

Horrell stayed because she received a full scholarship to attend the University of Missouri, and her parents said she couldn’t afford to turn it down.

One of the trends working against the re-establishment of Sharp End businesses is that it was soon followed by the integration of public accommodations, equal housing, and equal opportunity laws.

Horrell still won’t eat at Columbia restaurants picketed in the early 1960s because they would not serve Black customers.

A trend that could have made Black-owned businesses more visible but hasn’t is the influx of new residents that started in the 1960s. The population of Boone County grew 92 percent during the first sixty years of the 20th century. During that time, the number of Black residents of the county declined by 28 percent.

Since 1960, the Black population of Boone County has increased 453 percent, compared to a general growth rate of 232 percent. The most recent Census Bureau data shows Blacks are more than 10 percent of Boone County’s population, the largest share since 1930, and more than 12 percent of Columbia, the largest share since 1940.

The end of legal segregation, combined with affirmative action efforts in public employment, brought increasing numbers of new Black residents, Horrell said.

Barbara Uehling, MU chancellor from 1978 to 1987, brought Horrell in from her job in the School of Medicine to recruit Black graduates to return, she said, and the first Black alumni group was established. Black business ownership, however, doesn’t reflect that growth. The figures show most Black businesses remain small, with mainly part-time or minimum wage employees.

Census Bureau data shows there were 16,965 business firms in Columbia in 2021, with 3,465 of that number reporting one or more non-owner employees. There were 65,448 employees in private industry, an average of nineteen per employer and a total payroll of $3.4 billion.

Blacks owned 7.7 percent of all business firms, but only 98, or 2.8 percent, of the firms with at least one employee. Black-owned firms employed less than 1 percent of the workers employed in private industry and, with a payroll of $8.2 million, paid just two-tenths of a percent of the wages.

The average annual per-employee payroll in all Columbia businesses is $52,044. With an average of just over five employees each, the average per-employee payroll for Black-owned businesses is $15,077. Many of the Black-owned businesses in Columbia are the kind of personal services provided on Sharp End, Horrell said. They are less visible because they are scattered throughout the community.

“Blacks go all over town to get what they want,” she said. “There are none in the heart of Columbia anymore, except the Black barber shops.”

Warrick, who moved to Columbia for family reasons, said she noticed the lack of Black owned businesses compared to her hometown of Chicago.

“When I moved here it was different, because I wasn’t seeing a lot of Black businesses down here, and still don’t really to this day,” she said.

The Shops at Sharp End

You won’t be able to hear a jazz band, buy a pint of whisky, shoot a game of pool, or get a meal if you visit The Shops at Sharp End business incubator on the ground floor of the garage at Fifth and Walnut.

What you will find is an open space where designers offer clothes or a customizing workover for wedding dresses. Art for sale adorns the walls, and shelves offer books by Black authors, or their own works.

Opened in February 2024, the incubator established as a partnership of Regional Economic Development Inc. (REDI), the Downtown Community Improvement District, and Central Missouri Community Action’s Women’s Business Center, has struggled to find its footing, Warrick said.

It started with about twenty business owners offering wares but by the time she was hired in June 2024, it was down to nine, the current number.

Aaron Fox, a white writer of children’s books, said he was invited to take part during the initial creation of the shops and told it was designed to be a diverse place. He sells his books as well as stuffed animals and shirts he designs.

“The most attractive thing was being part of this community and being able to relate and be here and show my own things with other people,” he said.

The lingering resentment of how Sharp End was erased brings added friction to the creation of a new space in its name. Warrick said she’s tried to educate herself about what Sharp End was. She’s had panels come in for programs, including Horrell.

“I know how important it is to, not just the Black community No. 1, but for the Columbia community, period.” Warrick said. “I have a lot of people that come in and say, ‘I never knew you were sitting here. What is this about?’ And so I want to make sure that I am representing correctly.”

On the wall, written in cursive, are the words Sharp End. Horrell’s son recognized it as her handwriting, and she has concluded that the shops do not honor the memory of Sharp End and wants it taken down.

“I keep telling them, ‘Y’all need to take my signature down, because I have disassociated what you all are doing with what was originally up here,’” Horrell said.

Warrick hasn’t consented to take it down. There have been other complaints as well, she said.

“I have a lot of Black people that come in here and express their frustration about this particular program, or just this building itself,” Warrick said. “I’m not sure if some of the Black people that came in and expressed a frustration were supposed to be a part of the program, or either they gave input for the program and they felt like their input was taken away from them and someone else is getting credit for it.”

None of the entrepreneurs operating out of the shops has moved into a permanent location, Warrick said. But that is her goal.

“To see them have their own brick and mortar and be successful, that’s where I want to see them in five years,” she said.

Horrell said she wants to see more Black-owned permanent businesses in the space used by the shops, or, better yet, revive the idea that Rufus Logan had in 1901.

“If you built a big conglomerate right now of buildings that had spaces in it,” Horrell said, “you could get sixteen to eighteen businesses, Black businesses, right in there.”